[Listen above, read below, or both!]

Hello audio nerds! It’s good to be back. I’ve spent the past few weeks in Brazil for, um, research. And the music there did not let me down. More on that below.

If you’re new here, read The Charter. Today we’re welcoming 60+ new reader-listeners, so thanks to Substack for plugging Audio-First on the homepage.

One final note: all Audio-First editions are also findable on the podcast apps Apple/Spotify/Pocket Casts/Stitcher/others. (I prefer Pocket Casts because it displays the text fully linked in the Notes section. But you do you.)

Onward.

Lo-fi AR

Magic Leap, the bellwether company in augmented reality, is exploring a sale according to Bloomberg. The report suggests it could be for as much as $10B, which would be a healthy return on the $2.6B (!) it raised in equity financing.

But $10B is likely a stretch. Elsewhere, outlets like TechCrunch thinks this will be a fire sale. 2019 was a year of flameouts for well-funded AR startups like ODG, Meta, and Daqri. Additionally, Magic Leap suffered incredibly weak demand on its consumer headset and has since pivoted to enterprise, where it hasn’t found a foothold. If I were a betting man, I’d say this ends closer to a flameout, too.

This isn’t to poke fun, either. A lot of this tech will be crucial towards building AR, which feels all but inevitable as the smartphone successor. It’s just the consensus seems to have shifted, conceding that AR is further out than previously thought (more of a 5-10 year range).

This is a letdown to the startups and investors in the space. However, if AR’s timeline is now delayed, the opportunity for audio—with more time in the interim—increases a lot.

As I argued in my Betaworks presentation last year:

AirPods will likely be remembered as our first taste of transhumanism (we wear them all day & the sales are on par with iPhones so far)

AirPods could become a lo-fi AR or a low-fi Neuralink (it’s mostly a software problem now)

But so far, nothing we use them for is that novel (it’s all stuff we did with wired headphones)

Perhaps augmented reality’s current problems are audio’s fortune.

As the “interfaceless interface,” audio could offer many of the upsides of AR, except it’s here and now. We’re already wearing them all day long, as AR makers hoped for their headsets. And they can approximate a lot of real-time information from the smartphone (and maybe soon with head angles and gestures).

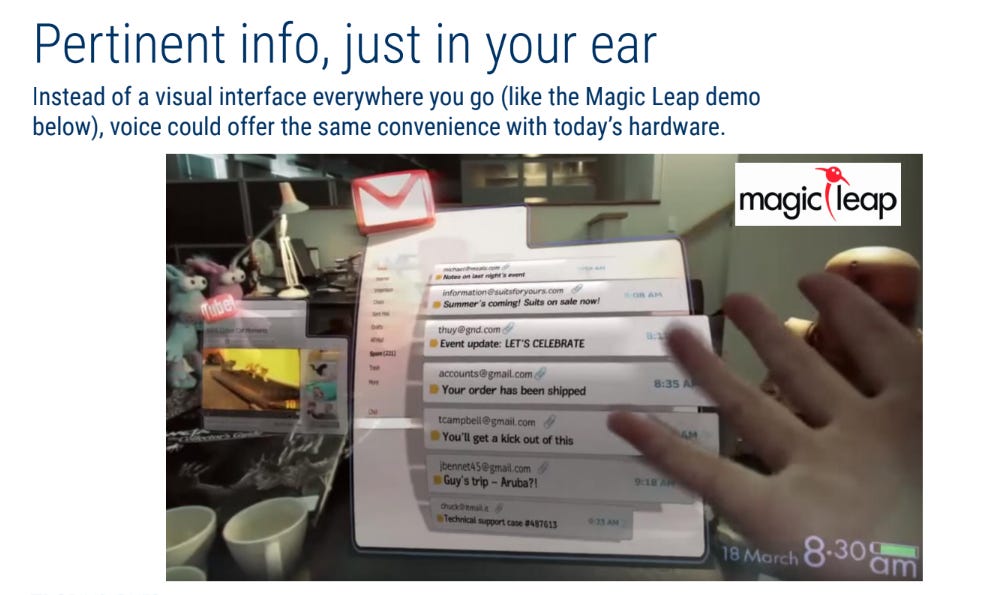

Second, the vision for AR headsets could be achieved, in part, with audio. It’s not difficult to imagine, say, 50% of the Magic Leap demos (like emails, basic search) could work somehow with today’s audio tech. The bottleneck right now is the smart assistant.

This is why I’m looking to Apple for any sign about where this goes. As I wrote in a previous Audio-First, the dictation of text messages on the AirPods Pro feels like that first taste of where audio is going:

Aside from noise cancellation, the biggest new addition is the native text message reading. (ICYMI - incoming iMessages are read aloud by Siri.) I love it. More and more, I find myself dictating messages out, especially when I’m outside running. It works fine enough, even if the Siri interaction is a bit slow. To me, it seems obvious that Apple will have a Siri-led category of new apps. It’s just a matter of when.

So far, Apple’s been quiet and has kept developer features with SiriKit pretty limited. But I suspect this will change in time. Additionally, Apple’s been rumored to be working on an AR headset for the past 10 years, and the reported ship dates keep getting pushed back (currently to 2023).

In the near-term, it looks like an even bigger opportunity for audio & AirPods. And amidst a work from home wave due to COV-19, I’d guess AirPods are spiking in demand. Perhaps we’re in a catalyzing moment.

Musica Brasileira

On the music front, Brazil was magical.

Granted, my most predictable travel habit is falling in love to the point where I browse Zillow, tell everyone back in NYC that "I could totally live there," and then never follow through. But Brazil, I swear, is a unique crucible for music.

My knowledge going in was more around bossa nova, which I understood as a beautiful jazz-samba fusion that pairs nicely with a pina colada. The reality on the ground was that, and a whole lot more. Bossa nova, samba, pagode (pronounced pah-go-jee, a sort of samba-folk hybrid), and tropicalia (psych-rock like Caetano Veloso) are probably the most exported music I encountered down there. Even my local friends there play it themselves. These are the “national” music genres.

Brazilian music, from what I learned in a documentary, has had a unique evolution, often fusing American music with its own unique sounds and instruments. To an American’s ears, it’s a wonderful degree of same-but-different. In culture and history, Brazil is not unlike America either. The most well-known genres have African roots and are steeped in a turbulent history of counterculture, political upheaval, and lasting inequality.

The contemporary party music, however, was something else entirely.

At parties and Carnaval events, people kept asking me what I think about the genre “baile funk” (pronounced “funky”). Baile funk, often just called funk, is basically the local equivalent of hip-hop, and I heard it everywhere. It has a distinctive cha-cha-cha-tik-cha beat that you can’t mistake, and culturally seems to occupy the same space as ratchet dancefloor hip-hop.

In a recent Guide to Urbano Music, Felipe Maia summarized funk’s history:

Between the 1950s and early 2000s, the population of favelas in Rio de Janeiro grew dramatically—the product of scarce public housing programs and unplanned urban expansion. At street level, the scenario was not so different from a subset of the South Bronx in the ’70s: a large, young, black population that wanted to party despite tough living conditions. This background laid the foundations for Brazilian funk, a genre that from its inception was deeply connected to club culture, also favoring danceable tracks, boiling-hot venues, and heavy soundsystems. DJ Marlboro was a high-profile figure in the early Brazilian funk scene, since he’d performed on many radio shows and gigs in Rio in the 1980s. In these sets, he dropped hip-hop anthems such as Afrika Bambaataa’s “Planet Rock” or DJ Battery Brain’s “808 Volt Mix,” which became rhythmic cornerstones for Brazilian funk (or, as it’s called in the U.S., baile funk).

It also turns out funk has its roots in American hip-hop and is currently going through a slot of the similar debates that hip-hop did:

Funk, which has roots in American hip hop, is performed mostly by men. Its critics say its lyrics promote misogyny, promiscuity and crime… A particular target is funk proibidão (taboo funk), in which explicit lyrics both glorify and lament violence. Funk ostentação (ostentation funk), which celebrates money and fame, is especially popular in São Paulo.

Sounds like a familiar story. If you really want to see the baile funk scene in action, watch this short documentary from Boiler Room. Some really wild footage.

After listening to my share of funk, some of it’s quite good. And some of it’s hard on the ears, or sounds hokey (e.g. the funk remixes of Old Town Road or A Star Is Born). But on the whole, it echoes urbano and hip-hop sounds that I know and enjoy.

Since leaving Brazil, I can’t help but wonder if some of this music is going to grow in popularity here. Anitta, who’s probably the biggest pop star in Brazil today, is a trilingual funk singer who’s starting to do crossovers with big names like J Balvin. (I’ve had her song Bola Rebola on repeat.) I also learned Diplo famously compiled funk mixtapes as a way to export the sounds and get Brazilian producers on the map.

After a Super Bowl in Miami, featuring Shakira and J. Lo, it’s pretty clear Latin music has arrived. I‘m curious what the future holds for Brazilian music, or if it can even be lumped into Latin trap. In my brief survey of people there, the impression I got was that Brazil doesn’t really consider itself Latin American. “It’s just Brazil,” was the common answer. (And almost nobody there speaks Spanish.)

In any event, the country is clearly brimming with musical life. Everyone I met seemingly had music talent. Somehow, I found myself participating in 3 of my 5 lifetime drum circles.

If you want a little starter pack, I compiled all my locally-recommended songs and Shazams into a playlist here. If you want to hear more Funk, try this. But if you listen to nothing else, I’d say try out Jorje Ben Jor, Novos Baianos, or Caetano Veloso.

Liner notes

Concert promoters suspend big shows around the world. New Four Tet and new Jay Electronica (feat. a lot of Jay-Z), making it feel very 2009. An interview with SZA. Apple WWDC will be entirely online.

Stay tuned and keep it locked. And stay safe out there!

Nick

FYI sampled songs: Tudo o Que Voce Podia Ser by Milton Nascimento, Bossa Nova Brasil by Joao Donato, and Marinheiro So by Caetano Veloso, and Bola Rebola by Tropikillaz.